Prince Alfred Copper Project

Prince Alfred Copper Project

Highlights

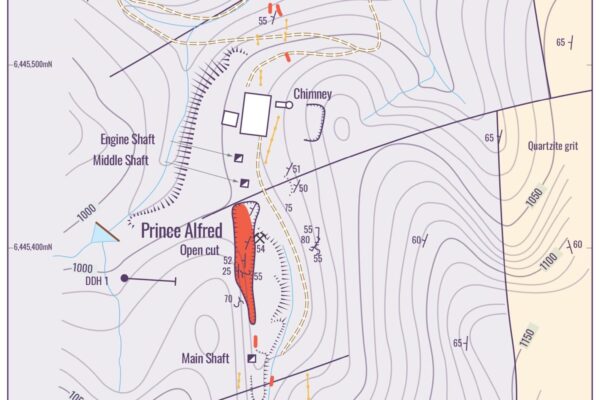

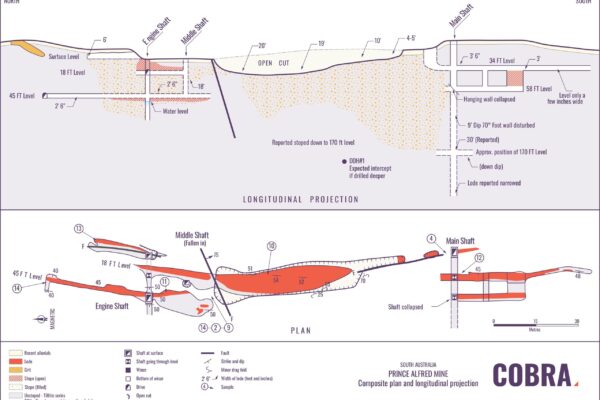

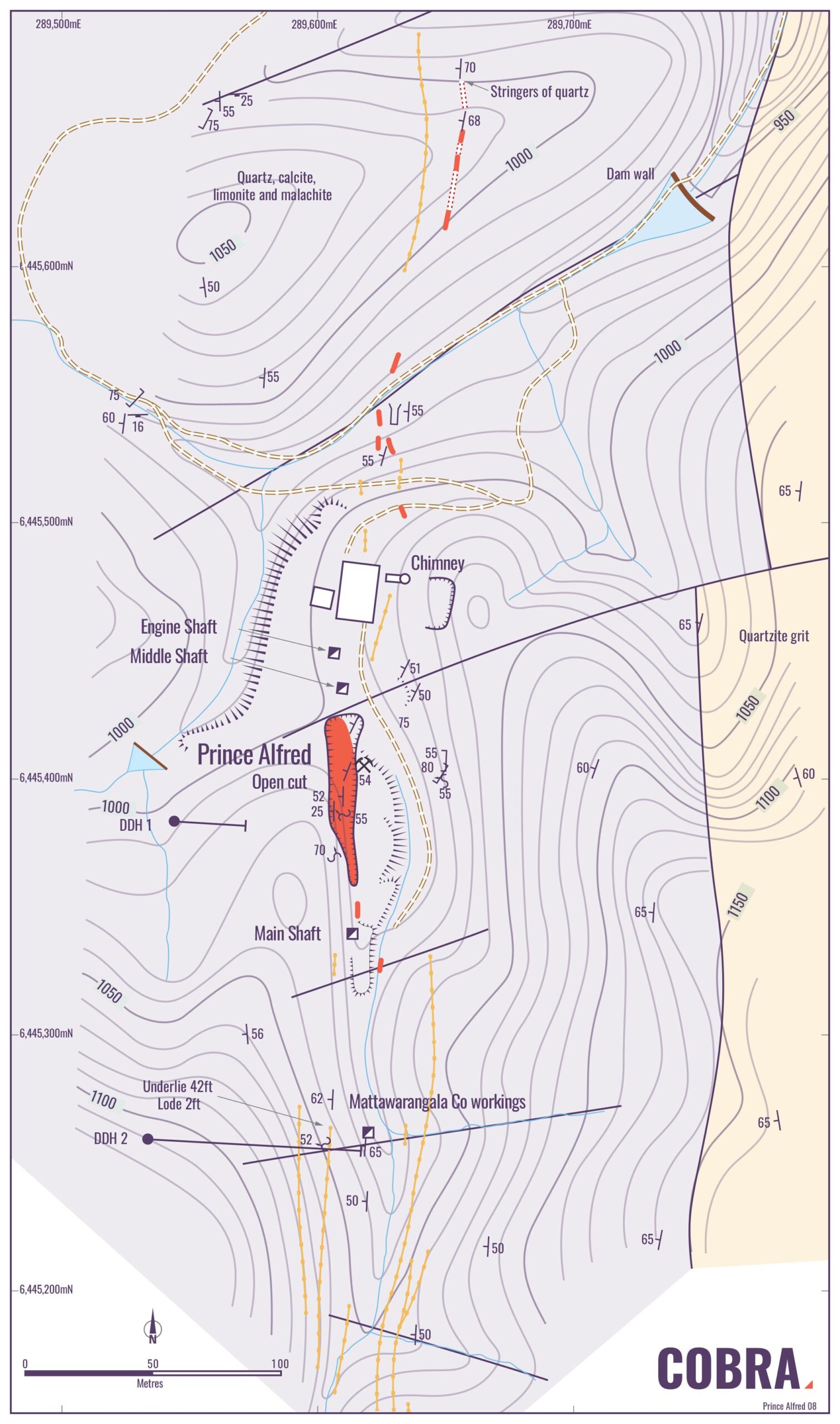

- Formerly producing copper mine (1907) located within the Adelaide Fold Belt

- Historic high-grade mineralisation reported as 3-5% copper

- Unexplored for over a century – depth or extent of mineralisation has never been properly tested – opportunity for exploration with modern technologies

- 100 km from Port Augusta, a prominent Australian transport hub city

Work to Date

- Original mine operated during the late 19th and early 20th century, recovering approximately 40,000 t of ore at 3-5% copper to a depth of 51m

- Mining ceased due to 1907 copper price crash

- Working EPEPR being developed

Ownership

Cobra Resources 100%

Exploration Licence:

Prince Alfred

Licence Area:

9 km2

Targets:

Copper